The Final Conference Illusions

Author: Mike Caveney

9 by 12 inches

154 pages printed in full color on heavy art matte paper

162 photographs

Printed endsheets

3-piece binding, gold stamped with leather spine

Published in 2023

Author: Mike Caveney

9 by 12 inches

154 pages printed in full color on heavy art matte paper

162 photographs

Printed endsheets

3-piece binding, gold stamped with leather spine

Published in 2023

Author: Mike Caveney

9 by 12 inches

154 pages printed in full color on heavy art matte paper

162 photographs

Printed endsheets

3-piece binding, gold stamped with leather spine

Published in 2023

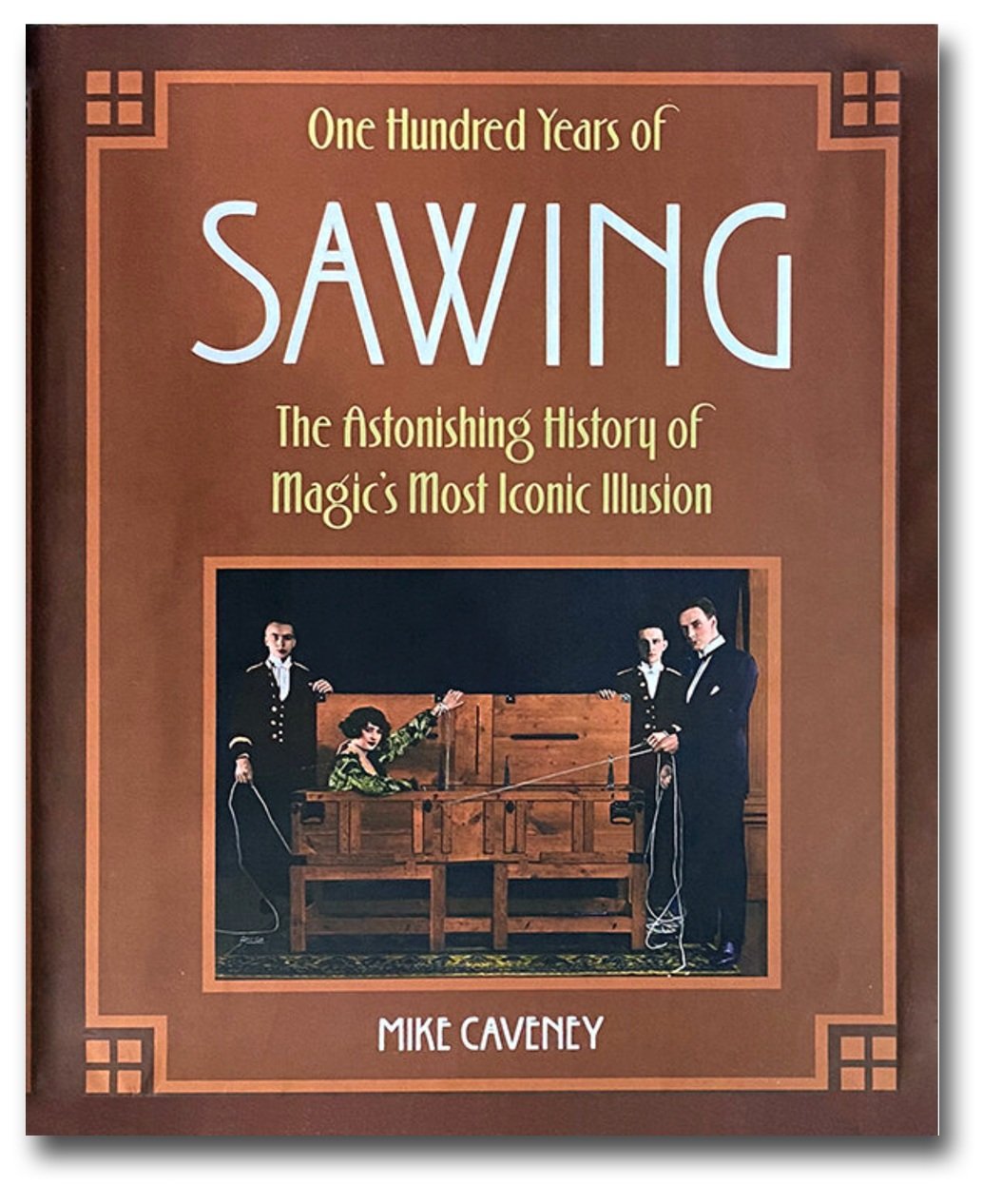

This beautiful, 154-page book provides a detailed description of the last three illusions that Mike Caveney presented at the Los Angeles Conference on Magic History including Carter the Great’s Spirit Cabinet, Rooklyn’s Birth of the Pearl, and John Daniel’s original Thin Model Sawing. Read the behind-the-scenes story of how these illusions were brought back to life along with their complete routines and patter. Mike’s performances of all three illusions are available on YouTube.

This book also serves as a companion to Sawing: The Astonishing History of Magic’s Most Iconic Illusion. Mike’s previous Sawing book focused on the history of this illusion while this new book delves into the original design and development of John Daniel’s, Virgil’s, and Walter Blaney’s versions of the Sawing. For the first time you can literally peek inside these classic illusions thanks to fifty new photographs that did not appear in the previous book. You will also find an entire chapter on the life of Zati Sungur, the man who invented the Thin Sawing illusion during the 1930s. His amazing career is brought to life through dozens of previously-unpublished photos.

9 by 12 inches, printed in full-color, hardbound with leather spine, and printed endsheets. Free postage for domestic orders.

“Absolutely sensational! Sitting down with it and reading it line-by-line while watching the corresponding YouTube videos frame-by-frame was truly one of the most fascinating experiences I have ever had in magic. I thought I knew a lot. Turns out that I didn't know jack shit. Reading about the pieces through both the magic effect and history lenses is the way to go for me. Brought me back to the LA History Conferences.” Andy L

“I’m only going to write this once, because I have the feeling I might need to write several times a day. They say when you know the method to a trick you will be disappointed at its simplicity. Well, I just read page 24. Absolutely ingenious! I’m anything but disappointed!” Larry H

Genii magazine review by Francis Menotti

If you take one bit of hard-earned knowledge from Mike Caveney's The Final Conference Illusions, it could justifiably be his idly tossed words in the foreword, "One cannot be afraid of failure. It's part of the process." This is a collection of successes that could only have been so due to overcoming challenges, changes, and downright failures. In this relatively compact volume, the author explores some of magic's golden era illusions and performers through historic accounts, personal anecdotes from folks lucky enough to have seen the illusions, and sometimes blind guesses formed by piece-mealed reconstructions of notes, props, posters, and photographs. These informed guesses, melded with modern know-how garnered from necessary stage-time, allowed Caveney to reenact some of the 20th century's iconic illusions at the LA Magic History Conference and for full week runs at the Hollywood Magic Castle.

John Lovick, who had the opportunity to assist the author in bringing some of these illusions to life, attests in his introduction, "Reading this book is almost as good as sitting in your living room, listening to Caveney tell stories." Caveney is one hell of a story-teller. Anyone fortunate enough to enjoy the pages painted with the wild and rich history of our art form will gain useful knowhow punctuated with dry, laser-precise wit that lifts the flavors of the stories to the surface so as to make them alive and fresh. These are not historical accounts, but timeless anecdotes that may as well have happened last week as last century.

This journey of magical exploration begins with Carter's "Spirit Cabinet" and the conjuring up of the historically famous spirit of a young girl, Katie King. In a matter of fact conveyance of the cabinet's construction and history, Caveney walks the reader through its original touring performance in all its bells and tambourines. Built by the Martinka Brothers in New York, one of the most eye-widening details of Carter's cabinet was its weight: 530 pounds! The author, through detailed text, posters, and photographs, fills several pages with how the cabinet was built and how it functioned in Carter's career, then delves into his own significant adjustments to bring the experience back to life for a modern audience in 2013. While most of the original functionality of the cabinet-its trap door, secret assistant shelf, and thread hook-up points could and would be used (mostly) in their original design, the author had to contend with the modern restrictions of the performance spaces in which he planned to reenact the piece. Among other changes was Caveney's understandable desire to shave a few pounds off the beautiful monstrosity by adjusting the design of the top of the cabinet. This became significant as part of the performance then and now was that the Carter "Spirit Cabinet" would be assembled onstage live in front of the audience, then disassembled at its conclusion. His adjustment to how the assembly occurred also made for a cleaner, more versatile method to sneak the hidden assistant-in this case the ever-skilled Tina Lenart-into and out of the cabinet.

To the reader who has yet to acquire and read this book, I would advise watching the You-Tube video of Caveney and company performing the piece at the Magic Castle before reading the rest of the explanation chapter. He includes a link to said video at the conclusion of the chapter, whereas the multiple methods used throughout the performance are all the more incredible if you have viewed it innocently, first.

After some more traditional or expected spiritual manifestations including the movement and disruption of bells, a tambourine, and a chair that are all flung about with abandon, the performer would ask the spirit of Katie King to show herself in a more physically substantial manner. The result: a sheer fabric-covered, slightly amorphous ghost-shaped something would fly from the open door of the cabinet out over the heads of the audience to the back of the theater, then turn around and return to its soon to be disassembled home.

While the rest of the methods and choreography of the Carter "Spirit Cabinet" are fascinating, Caveney's adjustments to make Katie King fly convincingly in a modern room for a modern audience is an adventure and education in ingenuity and determination. There is a creativity blockage moment that all great problem solvers encounter where they get stuck on a method because it is either technically good enough or would theoretically work, even though deep down there is the dreaded knowledge that there is a better way. In the explicitly detailed explanation of his solution to make Katie King fly, Caveney shares one of the more profound yet simple nuggets he picked up from being around David Copperfield's warehouse in the early developments of "Flying." That is, an object-or person-having agency over their direction makes the difference between floating and flying. With this haunting reality, the author worked out a method, abandoned it, and worked out an all new system that would meet the criteria for flying while allowing for repeatable performances and the use of only four other assistants and a stooge. Between the method and Caveney's charmingly cutting audience control verbiage to keep people from reaching up and touching the ghost only inches above their heads, the research and redevelopment clearly paid off as you'll see when you watch the You-Tube video.

The next segment of the book examines a piece that decidedly views better than it reads, and can also be seen again on Caveney's You-Tube channel. It is the long toured Chung Ling Soo (ne William Robinson) production of a woman, "Birth of the Pearl." A giant oyster shell on an ornate platform with dolphin-shaped legs finds its way to center stage when the magician and assistants open the pearl to show it empty, close it again, then it opens on its own to allow for the lovely human pearl to stand and reveal her existence.

True to Caveney's modus operandi in publication, he offers full but concise evidence as to the effect's history along with the lurid soap opera details that make these books so compelling to consume. As a reflection and callback to some of the shenanigans detailed in both the first Conference Illusions and Sawing, the reader learns of the unscrupulous nature of magicians-and tobacco companies-of yore. The first of said offenses occurred in the posthumous, unauthorized and uncredited publication of the details of "The Birth of the Pearl" by Will Glodston in his book More Exclusive Magical Secrets. But almost more egregious was the William Esty & Company advertising firm's decision to run ads for Camel cigarettes in which real and current illusions were exposed in print in advertisements under the title, "It's Fun to be Fooled." Subtext: it's more fun to know.

The rest of the historical examination of "Birth of the Pearl" makes its way around the globe with further stories of various builders taking, renaming, and performing a version or two of the illusion. After versions of it passed through the hands of a few other magicians, the original Chung Ling Soo illusion ended up in the hands of a friend of Caveney's, who subsequently kept it stored nostalgically in his garage. Caveney acquired the original prop when said friend's wife decided her "desire to park her car inside the garage far outweighed her dream of owning an antique illusion from the Golden Age of magic."

From there began the author's own determined quest to recreate "Birth of the Pearl" in its former glory. Though, as indicated earlier, the simple production of a woman from the seemingly empty shown pearl left a little to be desired. To this end, Caveney added a complex but beautiful "Floating Ball" sequence that has the payoff make an acceptable amount of sense and turns it into a genuine surprise when the live human is birthed from the empty shell and pearl. The description of method and execution of said "Floating Ball" is dizzying but impressive, with kudos to the amazing Christopher Hart for doing his Thing and being in charge of the handling of secret threads. Despite the effort to bring the classic back to life for a final hurrah, the author in so many words agrees with this reviewer's assessment as to how worthy of trouble the effect was to perform. The piece in question now lies quietly in David Copperfield's museum in Las Vegas.

The last almost half of The Final Conference Illusions plays to Caveney's life-long obsession with the complicated history of "Sawing in Half." As Lovick mentions in his introduction, the book acts almost as a sequel to both the first Conference Illusions and to Sawing. The latter becomes clearly undeniable as Caveney introduces the largely unknown, unsung Turkish magician Zati Sunger. Another wildly fascinating character from magic's past, Sunger was an avid magic enthusiast who ran off to Germany, against his parents' wishes, to become a submarine machine engineer. After being

stuck in Germany and unable to return home due to World War I, Sunger heeded the famed illusionist Alois Kassner's direct advice to take his magic full time. This spiraled into an impressive, international career which included, among other notable accolades, his own ahead-of-his-time creation of a thin-model "Sawing."

The author, having had early direct contact with Sunger and later with Sunger's daughter, takes the reader briefly through his life and his magical creations, including also an interesting "Cannonball Illusion" where a cannonball was shot through his assistant, and an amusing missing-finger trick where a duck bit his finger off live on stage. The last of these came about from Sunger losing said finger in a machinery accident and figuring he may as well make it part of the act. I won't spoil my favorite story of Sunger, but will tease it by saying we know there's film footage of his final performance in 1966. How he obtained it is an amazing testament to his drive and determination.

From Sunger, we move on to learn about John Daniel, the Pasadena youth who got into magic after seeing a botched "Asrah Levitation." Daniel, as a young man, created his own method for a "Thin Model Sawing," and sold the idea to Carl Owen in exchange for having it built. Daniel's unique adjustments of the false-feet mechanics and his clever geometric notion of how to steal an extra inch for the assistant to move in the box made for fascinating improvements to the woefully overdone illusion. We learn of Virgil and his dealings with Daniel and his assistance in affecting improvements on the trick. We experience a bit of the turmoil between Daniel and Les and Gertude Smith who came to buy into Owen's Magic, and then come to know that it was John Daniel's own performance of his "Thin Model Sawing" in 1963 that would inspire the author's life-long quest to know everything there is to know about "Sawing." Caveney then rounds out the chapter, and thereby the book, with a hat-tip and examination of the improvements made to "Thin Model Sawing" by the celebrated genius that was Walter Blaney. In Blaney's model, he refines the sloppily and unconvincingly executed method that Horace Goldin used a little over a half century earlier. The result was a deceptive sawing in half where both the head and feet were real despite there being seemingly nowhere for a second assistant to hide.

Unsurprisingly, the book is beautiful. The quality of printing and the incredible, colorful images complement the subject matter admirably. Mike Caveney is a story teller, and a truly magical one at that. The subject matter is inherently interesting to anyone already reading these words. But like a good illusion, it is all the more compelling, fascinating, and entertaining to learn about the Golden Age of Magic when the chosen words are filled with passion and personality the way they are in The Final Conference Illusions.

Ye Olde Magic Magazine review by Marco Pusterla

I can remember vividly the L.A. Magic History Conference of 2013: it was my first visit to what was the preeminent conference dedicated to the history of magic. I remember particularly Mike Caveney’s performance of Carter “The Great” original apparatus for the spirit cabinet. Sitting in the audience I saw the cabinet installed, surely with no opportunity to have anybody enter secretly and was surprised by the chair that moved on its own accord, the noise of the bell and tambourine and, especially, the “ghost” who floated out of the otherwise empty cabinet, passing over the heads of the audience, then incredibly turning around and flying back into the cabinet. As a historian, I knew that somebody had to be inside the cabinet and, knowing the principles of magic, I assumed that the assistant - the great Tina Lenert - had entered the cabinet from the backdrop. I also suspected that threads were the moving force behind the ghost, but observing the ceiling of the hotel’s ballroom, together with the other attendees, both before and after the performance, I could not see any thread. The mystery remained and I’m happy that Mike has now revealed it (together with another two illusions) in his last effort.

Years ago, Mike had published two large volumes, one describing his repertoire, the other explaining the illusions he had presented at the Conference on Magic History up to then, and this book, a much slimmer affair, is the third volume of this set. In addition to the explanation of Carter’s Spirit Cabinet, Mike explains his version Chung Ling Son’s “Birth of the Pearl,” wise sister us week jbiwbm g=which he presented in 2015 with the apparatus built by Chung Ling Son’s former machinist, which was last performed by Maurice Rooklyn in the 1950s. The third part of the book is dedicated to the history of the “thin sawing” illusion, invented by Turkish magician Zati Sungur in the 1930s, and that slowly entered the family of standard illusions via Tihany, John Daniel and Virgil. Mike performed this illusion, with John Daniel’s original apparatus, again in 2015.

The book is of interest to the historian, of course, but I believe the real student of performance magic will take great benefit by reading it. Mike explains everything in great detail, including all the small nuances of the misdirection, timing and materials for each illusion. I was flabbergasted in finally learning how the Spirit Cabinet worked: I had not thought that Tina could have been introduced to it with the devious method employed by Mike. The lesson on the use of threads, and on how Mike and his assistants introduced and removed them from the illusion during performance - and all the performances at The Magic Castle - is surely worth more than the price of the book.

Similarly, the study of the “Pearl” illusion and the decision of presenting a floating pearl before the production of Tina Lenert, shows how much an effect could be enhanced when thinking about it. Here, too, Mike offers some invaluable guidance on the staging of a floating ball in places where the room in the wings is not ideal… He has solved elegantly quite a few issues and enhanced the practicality of the rigging.

The last part presents a biography of Zati Sungur, enriched with unseen photographs of the magician, and details the story of his version of the “thin Sawing,” which had already been partially narrated in Mike’s recent book on the Sawing illusion. The apparatus of John Daniel and of Virgil are then described in detail, with many photos, showing the enhancements done to the illusion by the two magicians, going through a painstaking history of the construction of the boxes. A short chapter describes and explains the version of Walter Blaney which allows to have real feet in the box once the woman has been sawn in half.

Mike’s performances of these illusions are available on YouTube and I would suggest you watch them before reading their chapter, then watch them again, each being a masterclass on large illusions and their presentation. You should not make the mistake of thinking that Hugard, Soo, or Carter’s version of these illusions was as deceptive and as magical as Mike’s performance. In fact, these illusions were not as spectacular in the last century as Mike has made them Carter was keeping the cabinet close to the backdrop; Rooklyn opened the shell, closed it, opened it again and out popped an assistant. By knowing the history of magic, modern performers can improve and enhance tricks of the past and make them much more magical than they ever were.

I highly recommend this book to any magic historian and also to performing magicians - for them, this could be a great investment.